A University of Louisiana at Lafayette researcher has uncovered the first direct evidence of a rare chemical process deep inside an exploding massive star by analyzing ancient stardust billions of years older than our sun.

The discovery, led by Dr. Ishita Pal in collaboration with an international team of researchers, was published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters. The findings answer a longstanding question in astrophysics: where do certain rare chemical ingredients in our universe come from?

“This is the first direct evidence that certain rare isotopes are created and thrown into space when massive stars explode,” said Pal, who earned her Ph.D. in earth and energy sciences from UL Lafayette in 2025 and is now a postdoctoral researcher in its School of Geosciences. “These grains are like time capsules. They carry the chemical signatures of stars that lived and died before the sun formed and preserve clues about the extreme conditions inside those stars.”

The stardust survives today as microscopic presolar grains — tiny mineral fragments that formed before the solar system and preserve the chemical fingerprints of long-dead stars.

The rare chemical signatures were found in ancient cosmic dust preserved in the Murchison meteorite, which contains some of the oldest material in the solar system. The dust grains — some thousands of times smaller than a grain of sand — formed around dying stars long before the sun and planets existed. They became trapped inside the meteorite, which fell to Earth in 1969.

Pal and fellow researchers studied a specific type of presolar grain made of graphite — the same material used in pencil lead — and found something never detected before: five microscopic particles containing unusually high amounts of a rare form of strontium known as strontium-84. That chemical pattern can form only inside massive stars shortly before they explode as supernovae.

To make the discovery, the team used a specialized laboratory instrument capable of measuring the chemical makeup of extremely small samples. As the grains were analyzed, the instrument detected sudden bursts of strontium signals that revealed tiny particles hidden inside the larger grains.

The chemical fingerprints did not match anything produced by the types of stars that typically supply this kind of dust. Instead, the researchers showed that the only source consistent with the evidence is the violent inner layers of a supernova, where intense heat and energy forge rare forms of chemical elements. That material then mixed with carbon-rich gas farther out in the star, where the stardust eventually formed.

Dr. Brian Schubert, director and professor in the School of Geosciences in the Ray P. Authement College of Sciences at UL Lafayette, said the finding combines scientific importance with a sense of wonder.

“The collection, measurement and identification of stardust from outside our own solar system is the kind of discovery that captures people’s imagination,” Schubert said. “Dr. Pal led a collaborative, international team to measure these tiny grains within a meteorite and found a chemical signature that cannot be explained by processes within our solar system. She concluded these grains originated from a cataclysmic explosion of a very large star — something scientists have modeled for years, but never directly observed.”

Pal is a NASA FINESST Fellow, an award supporting outstanding graduate research aligned with the agency’s science missions. She said the discovery shows how tiny grains of dust can help answer some of the biggest questions in our universe.

“These grains are physical pieces of stars that lived billions of years ago,” she said. “They survived the violent birth of the solar system and now help us understand how the elements that make up planets — and life — were created. This is truly about tracing our cosmic origins.”

The study included researchers from UL Lafayette, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, Clemson University, the University of Wisconsin–Madison and institutions across Europe and Australia.

The full study is available here.

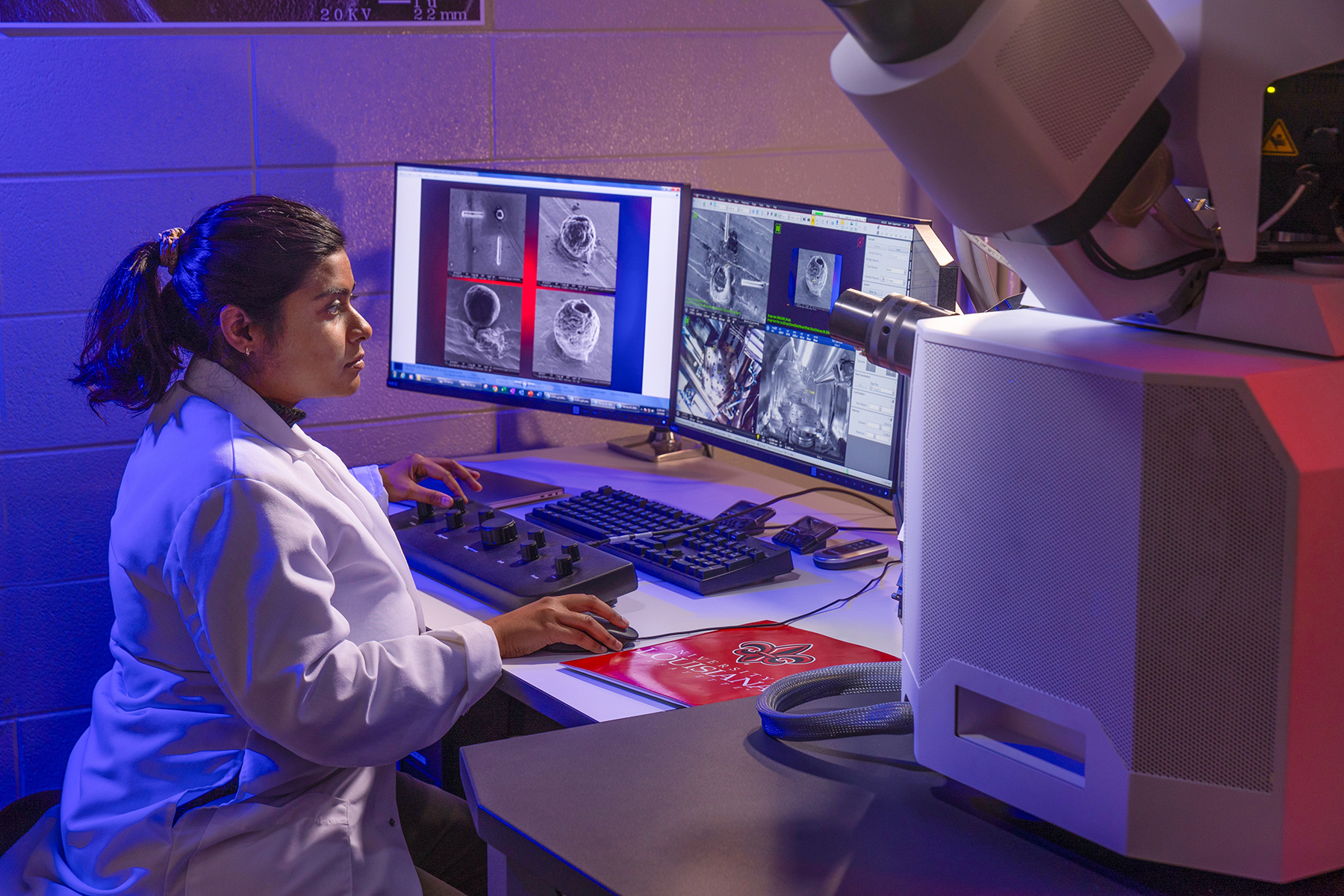

Photo caption: The University of Louisiana at Lafayette’s Dr. Ishita Pal led an international team of researchers who uncovered the first direct evidence of a rare chemical process inside exploding massive stars. (Photo credit: Doug Dugas / University of Louisiana at Lafayette)

UL Lafayette researcher reveals first direct evidence of rare cosmic process in ancient stardust

Published