The University of Louisiana at Lafayette’s College of Nursing and Allied Health Professions has earned national recognition as a pioneer in end-of-life care education.

The End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium recently inducted the college into its Hall of Fame. The University’s nursing program is one of 100 nationwide – and the only one in Louisiana – to achieve that designation.

The College of Nursing and Allied Health Professions has been teaching students about end-of-life care since the late 1990s. By 2004, it was one of the first nursing colleges in the nation to use course content developed by ELNEC. The consortium’s curriculum is the only one endorsed by the American Association of Colleges of Nursing.

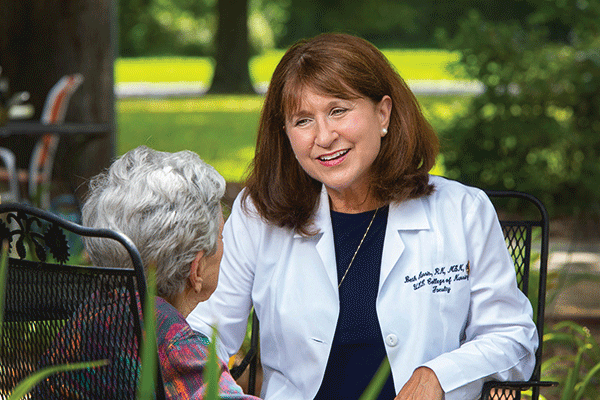

Beth Harris, a master instructor in the college, has taught the Palliative and End-of-Life Care course for 11 years. She said the consortium requires nurse educators to use the latest research-based material.

“I don’t use a text for the classroom because ELNEC gives you the most up-to-date information and has required readings,” Harris said. The College of Nursing and Allied Health Professions’ elective course is a hybrid that alternates traditional classes on campus and online sessions.

Harris is quick to point out that palliative care is not synonymous with hospice care for terminally ill patients. Palliative care is “for anyone with a life-threatening or chronic illness. You anticipate, prevent and treat suffering. It promotes quality of care, holistic care, treating the spiritual, the psychological, the social and the physiological needs of the patient. You treat the whole patient,” she said.

So, nurses may introduce palliative care when a patient learns that he has a chronic, life-limiting condition or begins an intensive treatment regimen, such as chemotherapy.

“A palliative care nurse may come in and just talk to that patient when he’s not in crisis,” Harris said. That conversation may cover advance directives, such as living wills that express what kind of health care patients want if they are unable to communicate.

Harris noted that end-of-life care isn’t restricted to a patient. “It’s the patient and the family, a unit of care. The ‘family’ may not be a family member. It may be the caretaker or someone who is very close to the patient and the family.”

When Harris and Dr. Melinda Oberleitner, dean of UL Lafayette’s College of Nursing and Allied Health Professions, attended nursing school and started their careers, end-of-life care courses weren’t offered.

Nurses and physicians were taught to save lives, to extend lives and to help patients feel better, Oberleitner said. “You didn’t talk about dying.”

With advances in technology and the advent of procedures such as CPR, medical personnel were able to extend the lives of more patients.

Improved oncology treatment prompted a shift toward chronic care and, in some cases, palliative care. As cancer patients began to live longer, treatment began to focus not on just combating the disease, but on improving quality of life.

Over the years, ELNEC’s curriculum has expanded to include the introduction of palliative care at a much earlier stage in an illness.

Harris said this approach introduces palliative care upon diagnosis of life-limiting or life-threatening illnesses and active treatment. “A palliative care nurse may come in and talk to that patient when they’re not in crisis. That nurse may ask, ‘Have you ever thought about advance care planning, about having a living will?’”

Communication with patients who are grappling with long-term, non-curative illnesses or imminent end-of-life issues is key.

Oberleitner said the Palliative and End-of-Life Care course teaches nursing students how to have conversations with those patients.

“It’s called a crucial conversation to have at the end of life or with a patient who is experiencing a life-threatening illness. That’s something that you need to be educated about how to do. It’s a skill,” she said.

Harris noted that a large component of end-of-life and palliative care is simply listening. “A lot of it is saying nothing, doing nothing, but just being present.”

(Editor’s note: A longer version of this story appeared in the Fall 2019 issue of La Louisiane, the magazine of the University of Louisiana at Lafayette. Read the full article in the magazine’s digital edition.)

Photo caption: Beth Harris, a master instructor in the College of Nursing and Allied Health Professions, has been teaching a Palliative and End-of-Life Care course for 11 years. (Photo credit: Doug Dugas/University of Louisiana at Lafayette).