A pair of scientists, including a biologist from the University of Louisiana at Lafayette, has countered a long-held theory that king snakes suffocate their prey.

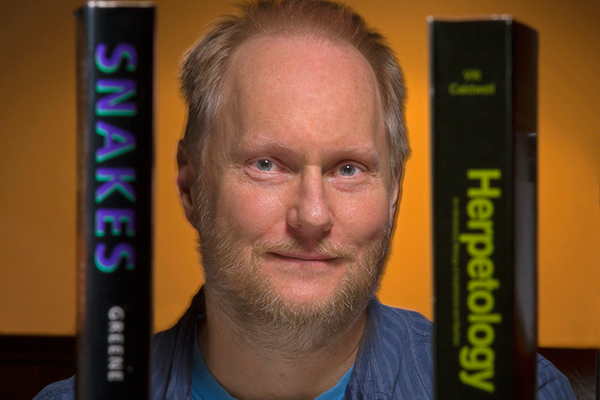

UL Lafayette’s Dr. Brad Moon and Dr. David Penning, a biologist at Missouri Southern State University, have tested how the snakes overcome their victims. Penning is a former UL Lafayette doctoral student.

King snakes are native to North America and have evolved into the strongest constrictors in the world, with the ability to exert 180 mm Hg of pressure. That’s about 60 mm Hg higher than the healthy blood pressure of a human being.

With such force, king snakes aren’t taking their victims’ breath away. They’re restricting blood flow—and that’s a major breakthrough in how scientists understand the relationship between predator and prey in the reptile world.

Moon and Penning’s conclusions are featured in this month’s edition of the Journal of Experimental Biology. Their study also received attention last week from National Geographic.

The king snake’s ability to cut off blood flow in its victims has given the reptile something of an arrogance in the wild, the researchers concluded. The snake has ceased to play by the old rules that say a smaller predator avoids a larger prey.

In fact, a king snake can use its killer squeeze to neutralize and eat other snakes up to 20 percent larger in size.

When the scientists matched a king snake versus a rat snake, the smaller king snake picked a fight, Penning told National Geographic. “They actively and directly will attack a larger individual. That’s not normally what’s expected across basically all of animal diversity.”

The constrictor study isn’t the first time Moon and Penning have proven a perennial theory about snakes incorrect—and received national publicity for it. A study they conducted last year showed that venomous rattlesnakes and other vipers do not, as previously thought, strike faster than their nonvenomous brethren.

UL Lafayette doctoral student Baxter Sawvel also collaborated on the project, which received notice from National Geographic, the Los Angeles Times, The New York Times and Discover, among other publications.

Read more about Moon and Penning’s latest conclusions at http://news.nationalgeographic.com/2017/03/snakes-constrictors-kill-predators-muscles/