Cheylon Woods, left, director and archivist of the Ernest J. Gaines Center at UL Lafayette, is seen with Dianne Gaines, the author’s widow. The international center for scholarship on Gaines and his fiction is housed in Edith Garland Dupré Library. La Louisiane asked Woods to share her thoughts about Gaines’ legacy as an author and teacher.

"Thank you for taking care of my words."

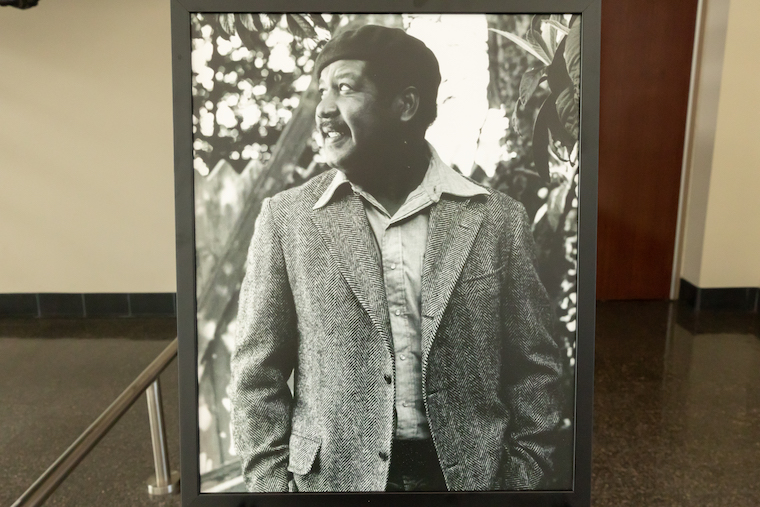

Ernest J. Gaines drew inspiration from a deep sense of love and commitment to the rural landscapes and culture of his childhood. Growing up on Riverlake Plantation – the same plantation where his family had been enslaved – Dr. Gaines learned many transformative lessons of resilience and steadfastness in the face of systemic oppression.

The elders around him were pillars of their community and worked hard to encourage pride, self-determination and self-respect in the children and young adults around them. Despite abusive and racist laws specifically created to discourage the education of Black children, the adults of Cherie Quarters did what they could to encourage and support the education of Ernest Gaines and the other children of the plantation. It was this love and dedication to education and endurance that encouraged him to write and to train those who wanted to learn.

Dr. Gaines joined the faculty of the College of Liberal Arts in 1981 as the University’s first writer-in-residence. During his tenure, Gaines helped many students find their narrative voices and put their passions to paper. His ability to encourage and nurture someone’s passion, I believe, was one of his strongest traits.

While he was receiving accolades the world over, he never lost sight of the beauty and complexity of south Louisiana. Through his students, colleagues and readers, he penned intricate portraits of a time gone by, but that remained very near and ever-present throughout the South. He shared his love, his muse, with the world and, in turn, the world learned to find ways to share its muses with others. He crafted narratives around characters who were so amazingly human – not good or bad, just beautifully human in complicated and sometimes heart-wrenching circumstances, and he still built within them hope and dignity. Through his work we all learned to recognize and respect the universal struggles we all endure, and we learned to live truthfully to our causes.

My fondest memory of Dr. Gaines is the first time I met him in person. I was so nervous. I made my husband turn around multiple times because I kept forgetting things, and I wanted to make a good impression. Not only was he a kind and generous man, but he and Mrs. Gaines became my biggest supporters throughout my time at the University.

An inscription he wrote to me in a copy of The Tragedy of Brady Sims reads: “Thank you for taking care of my words.” As an archivist, that short sentence is so edifying. His support is what inspires and fuels my career, and every day I hope I am making him proud.

Wiley Cash enrolled at UL Lafayette to study under Ernest J. Gaines, the internationally acclaimed author and the University’s writer-in-residence. Gaines, who died in 2019 at age 86, taught creative writing at the University from 1981 until his retirement in 2010. Cash proved an apt pupil. On his way to earning a doctoral degree in English in 2008, Cash began A Land More Kind than Home, the book that would launch his career. It was published in 2012. Gaines, for one, was impressed. “Wiley Cash is a talented and disciplined young writer. I think this could be the beginning of a long, fruitful career,” he wrote in praise of Cash’s debut novel. Gaines was right. Cash is the bestselling author of five novels, owns a pile of literary awards, and is writer-in-residence at UNC Asheville in his native North Carolina. Earlier this year, Cash returned to his alma mater, where he spoke during the U.S. Postal Service’s official commemoration of its postage stamp honoring Gaines. Here is Cash’s tribute to his mentor and friend.

I met Ernest Gaines in person on my first day as a graduate student at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette. When I entered the English department office in Griffin Hall he was standing near the mailboxes, speaking to another professor. I was instantly aware of him being nearby; both the brightness of his personality and the gravity of his presence were akin to the effect that the sun has on the planets in our solar system. At least that was his effect on me. See, I’d first met him through his fiction as an undergraduate at the University of North Carolina Asheville, and I’d decided to attend graduate school at UL purely because he was the University’s writer-in-residence.

The book I had read was Bloodline and, in those stories, Gaines had not only written about his own life, his own people, and his own place, but he had also written about mine. How was this possible? How was it possible that a Black man from south Louisiana who was born on a plantation between the wars had written in a way that so clearly spoke to the experiences, hopes, dreams and fears of a middle-class White kid from western North Carolina who was born in the early years of the Carter administration? Gaines had done what all great writers do: he had removed the barriers that would keep someone like me from perceiving the realities of life for someone like him and, in doing so, he had shown me the realities of racism, geographic isolation, cultural pride, class division and historical injustice in ways that I otherwise would have never known.

More than a decade after meeting Ernest Gaines, after becoming his student, his mentee, and eventually his friend, I was named writer-in-residence at the university in North Carolina where I had first fallen under the influence of his writing. It would be easy to say that my connection with him had come full circle at that point, but that full circle implies some kind of closing, and his influence on me and my love for him and his wife Dianne has no end, so there is no circle, just a continuing unbroken line from him to me and from me to the students of my own with whom I have shared his work and his influence on me. So, for him to receive the honor of a postage stamp with the word forever on it seems incredibly fitting, at least for me, because I will forever feel the gravity of his presence as it bends me toward him, I will forever see the light of his work as it leads us forward, I will forever hear the sound of his laugh and the clarity of his voice both on the page and off.

About Ernest J. Gaines

Born: Jan. 15, 1933, in Oscar, La.

Books: Catherine Carmier (1964); Of Love and Dust (1967); Bloodline (1968); The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman (1971); A Long Day in November (1971); In My Father’s House (1978); A Gathering of Old Men (1983); A Lesson Before Dying (1993); Mozart and Leadbelly: Stories and Essays (2005); The Tragedy of Brady Sims (2017)

Filmography: “The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman” (1974); “The Sky Is Gray” (1980); “A Gathering of Old Men” (1987); “A Lesson Before Dying” (1999)

Awards & Honors: Wallace Stegner Fellow (1957); National Endowment for the Arts grant (1967); Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation Fellow (1971); National Book Critics Circle Award for Fiction (1993); nominated for Pulitzer Prize (1993); John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Fellow (1993); Dos Passos Prize (1993); Chevalier of the Order of Art and Letters (France, 2000); American Academy of Arts and Letters Department of Literature (2000); National Humanities Medal (2000); the F. Scott Fitzgerald Award for Achievement in American Literature (2001); Sidney Lanier Prize for Southern Literature (2012); National Medal of Arts (2012)

Died: Nov. 5, 2019, in Oscar, La., at age 86

Photo credits: Doug Dugas / University of Louisiana at Lafayette

This article first appeared in the Spring 2023 issue of La Louisiane, The Magazine of the University of Louisiana at Lafayette.