Researchers at UL Lafayette’s New Iberia Research Center have conducted a vaccine trial on chimpanzees that could help protect endangered wild apes from deadly infectious diseases, such as the Ebola virus.

It’s believed to be the first time that a vaccine intended for apes – rather than humans – has been tested on captive chimpanzees. Results of the trial are published in the latest issue of Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Vaccines haven’t been used to fight outbreaks of diseases in chimpanzees and gorillas because of concerns about their safety, according to the journal article.

But Dr. Joe Simmons, NIRC director, said high mortality rates have made many conservationists more receptive to the potential protection of vaccines.

“Preserving endangered chimpanzee and gorilla species is a common cause for conservationists and medical researchers,” he said.

NIRC researchers tested a virus-like particle vaccine, which contains a small amount of viral proteins but is incapable of replicating. “The vaccine doesn’t cause infection, but it does cause an immune response to those proteins that can protect against infection,” Simmons explained.

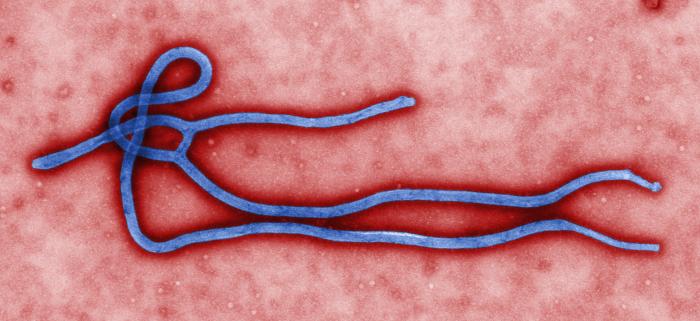

Ebola is a particular concern. Along with commercial hunting and loss of habitat, it is decimating wild gorilla and chimpanzee populations. It is one of the leading killers of wild apes.

“Ebola is one of the hemorrhagic fever viruses. It has a very high attack rate and very high death rate,” Simmons said.

The virus is also deadly for humans.

A recent outbreak of the Zaire strain of Ebola in West Africa has caused more than 250 documented human cases, which have resulted in more than 175 deaths since March in Guinea and Liberia. This week, four deaths in the Sierra Leone region of West Africa have been confirmed, according to the World Heath Organization. The disease is transmitted through human contact and through consumption of animals that have contracted Ebola.

Chimpanzees at the NIRC were tested for the Zaire strain of Ebola, Simmons said.

Researchers determined that apes given the virus-like particles and an adjuvant, which is a substance that enhances immune system response, developed enough resistance to survive the Zaire strain.

“We demonstrated that they had antibodies that would be protective,” Simmons said.

Chimpanzees and gorillas are susceptible to a host of pathogens, including malaria and simian immunodeficiency virus.

“The findings of the vaccine trial conducted at NIRC are important because it’s crucial to protect primate species in the wild from extinction,” Simmons said.

The NIRC is collaborating with VaccinApe, a non-profit organization working to implement vaccination for the endangered animals.

The center is in New Iberia, La., about 20 miles from the University of Louisiana at Lafayette’s main campus. It houses more than 6,000 nonhuman primates, including about 200 chimpanzees.

In the past, the NIRC partnered with the pharmaceutical industry and the National Institutes of Health to develop vaccines for the prevention of human diseases, such as Hepatitis C and Respiratory Syncytial Virus.